Published in 2010

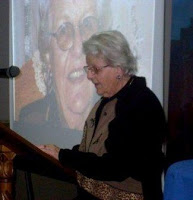

Emerson – Her hearing and eyesight fading, Alice Khachadoorian-Shnorhokian's body may betray her age, but her mind is still sharp, her memories still vivid.

At 97, Alice is one of the last few remaining survivors of the Armenian genocide. A resident of the Emerson Armenian Home for the Aged, she sits with a blanket draped over her legs and recalls the story of her family's survival in 1915.

The 95th anniversary of the genocide falls this Saturday. It will be marked with a gathering in Times Square April 25 to remember the more than 1.5 million Armenians killed by the Young Turks of the Ottoman Empire. Armenians mark April 24, 1915 – the day hundreds of intellectuals were rounded up, arrested and later killed – as the beginning of the genocide. At the time there were more than 2 million Armenians living in the declining empire. In just six years their numbers had dwindled to fewer than 400,000.

Alice was 3 years old at the time the genocide began. Her family, wealthy evangelist Christians, lived in a "castle-like" home in Aintab, Turkey when they were given deportation orders.

Her mother tried to bribe the governor's wife, but the governor would only allow Alice's father to escape. He would not leave the family.

Along with thousands of others, Alice, her parents, and her siblings were driven over mountains and through deserts on a forced death march from village to village without food, water, or shelter.

"I was too young to walk, but everybody had to walk," Alice says. "My brother was also too young, so my father bought a donkey and put two seats on both sides of the donkey and put us in the box."

She remembers being so hungry that when she spotted a watermelon rind on the ground in one village she picked it up, trying to see if there was anything edible left on the hard shell.

From her basket atop the donkey, Alice witnessed terrible things. "We walked over the dead, young boys and girls. We travelled over people shouting and crying to die," she recalls.

They reached the last village of Meskene, Syria before travelling to the final destination – Der Zor – the Syrian desert where hundreds of thousands of Armenians were executed in killing fields and concentration camps. "The day we were going to the desert, my father put down the tent and then we prayed," she says. "We sang and asked God to help us."

Their prayers were answered. A friend in Meskene bought permits to save them. They were allowed to leave the march, and the man gave Alice's father, an operator of a caravan in Aintab, a job.

Not everyone in the family was so lucky. One of Alice's uncles was shot. After he was killed, his wife was shown his gold watch, and told, "Your husband is dead now. Now you can marry us." She refused. She was thrown into a ditch with other young women, covered with gasoline, and burned to death.

When they returned to Aintab after the 1918 armistice, the family found their vineyards and farms had been taken. Robberies and killings were commonplace. "They would come at night and kill and rob. We were not safe," she says. "There was lawlessness."

The family fled to Aleppo, Syria, which was controlled by the French government after the partitioning of the Ottoman Empire.

Because of her mother's ingenuity, the family was able to rent a house instead of sleeping in barracks, as many Armenians did in Aleppo. In Aintab, she would use the well outside the family home for drying vegetables. Before leaving for Aleppo, she put the family's savings inside a dried pepper, and put the pepper in a bag of food to take on the journey. If the driver was aware of the small fortune his passengers carried, he likely would have killed them for it, says Alice. Instead the money was used to rent a house and pay for each child's education. "Necessity is the mother of invention," she says. "You invent, there's no other way to exist."

Later, after Alice completed high school, the family moved to Beirut, Lebanon. There she got her degree in nursing from the American University and worked as a midwife, often travelling by bicycle to deliver babies in their homes. She married a pastor in 1942 and moved to the United States in 1980 where her three children completed their studies.

Armenians have pressed the U.S. Government for decades to officially recognize and condemn the mass killings of Armenians during World War I as genocide.

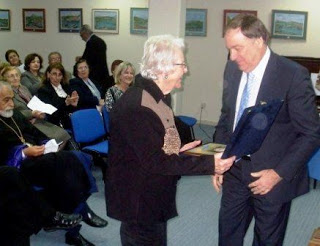

In 2008, Alice visited Washington D.C. with Rep. Scott Garrett to speak personally with members of Congress and push for recognition and justice. She wants people to acknowledge the atrocities of the past, she says, so they are never repeated.

"I remember it clearly," Alice says. "Everything is rotten. My hearing, my eyes, my body is failing, but God gave me a brain to remember. This is a special grace."